-

Written by Kathryn Stockton

Written by Kathryn StocktonFrom performance marketing to operations, Kathryn has in-depth experience in marketing and a background working in digital advertising agencies.

Marketing is one of the fastest adapting roles out there - digital advertising, media buying, and performance marketing in particular. The role of a modern marketer is now unlike anything from the old Madison Avenue days. I would argue if we were to drop a digital marketer from 2018 (not that long ago) into a modern-day Google Ads account, they would be lost without thousands of keywords to granularly optimize.

And the pace at which digital marketing is evolving has brought rise to a wave of exciting discussions:

- How will marketers adapt to a cookie-less future?

- What skills should marketers develop to prepare for the future?

- What key levers can marketers pull with black-box campaigns such as performance max?

One such topic, which seems to have taken a temporary backseat while cookies steal the limelight, is the metrics we use to understand performance. There are many we can look at, and many we can optimize on, which leaves marketers with the question - what metrics matter? Let's take you on a journey from CPC to CPA to ROAS and beyond.

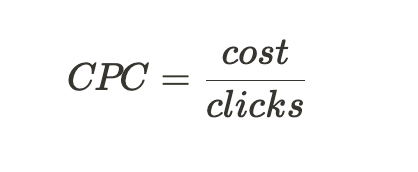

CPC

Back in the days of AdWords and keyword-level optimization, CPC was king. Our Cost Per Click was one of the best measures of efficiency. But, while it told us how cheap our traffic was, it failed to consider the quality of each user clicking on an ad. For example, if you sell high-end furniture, would you rather get a lot of traffic with low CPCs and people not interested in converting? Or would you pay more per click for luxury consumers with cash to spend?

CPC is and will always be a metric we monitor as it can help us understand competition or the impacts of changes we make to platforms. Beyond this, there is not much value that CPCs can offer anymore.

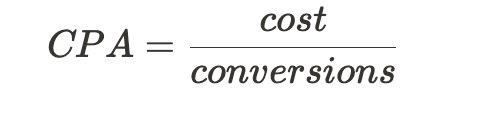

CPA

With better conversion tracking and wanting more users to carry out quality actions on websites, we started to optimize on conversions. Cost Per Acquisition (or Cost per Action) became the key marketing metric, and campaigns were switched to generate as many conversions as possible.

While generating conversions is a worthy goal, not all conversions are equal. Consider being an e-commerce company selling clothing. One pair of socks is not equivalent to selling the latest designer jacket, and yet when we optimize to CPA, we lose sight of the different revenue they bring.

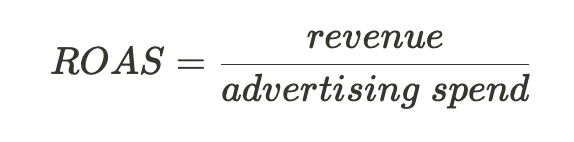

ROAS (Return on ad spend)

ROAS was an evolution beyond CPA as it allowed campaigns and marketers to understand better the revenue they were driving.

ROAS is the advertising-specific version of ROI - which isn’t very helpful as a definition if you are also unfamiliar with ROI. ROAS stands for Return On Ad Spend and ROI is Return On Investment. To simplify ROAS, we measure how much we make for every dollar spent on ads. Some marketers calculate it as a percentage, others in their local currency, or it can just be a normal number. As a calculation, we take our advertising revenue and divide it by our advertising spend.

As with CPA, we use ROAS to understand which campaigns, ad groups, or ads drive the most bang for our buck.

ROAS formula

A quick point to stress here is that your ROAS should be greater than 1, any less and you are spending more on ads than you are making in revenue.

Also, it is not easy for some businesses to know how much revenue your advertising campaign generates in a specific period. For instance, a B2B construction company uses an ad campaign to generate leads. As it may take months before a lead drives revenue, you will need to come up with a monetary value for each conversion on your website to calculate ROAS.

ROAS, CPA, and CPCs matter. They are the usual suspects regarding reporting and optimization, but they don’t consider the more long-term, strategic business goals.

Moving away from ROAS, CPA, and CPCs

Although some marketers use ROAS as a north star, it is not the one metric to rule them all. There are better metrics out there, and the reason is threefold.

- ROAS is decoupled with volume

- ROAS focuses on short-term revenue

- ROAS assumes perfect attribution

To adjust your reporting, I’ll dive into these issues with workarounds or new metrics.

Problem 1: ROAS is decoupled with volume

Let’s get somewhat technical and talk about issues with volume and incrementality.

But before we do, a quick shout out to Fred Vallaeys from Optmyzer for giving a great talk on the anatomy of the modern marketer and introducing this concept of incrementality with ROAS.

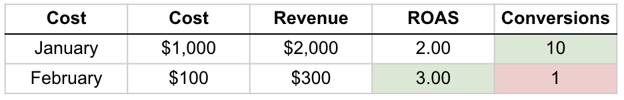

Imagine that you’re the CMO and your team reports that your ROAS is at a new high of 3 this month - great! But then you have the sales team at your door complaining that sales are much lower than last month. If you only focus on ROAS, you can lose sight of other metrics and start sacrificing on volume. This example below is exaggerated but helps highlight a potential pitiful for marketers:

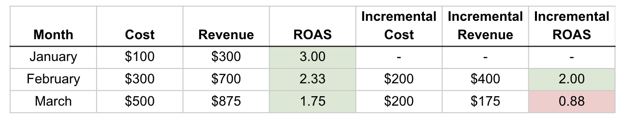

January had a lower ROAS, but more revenue.

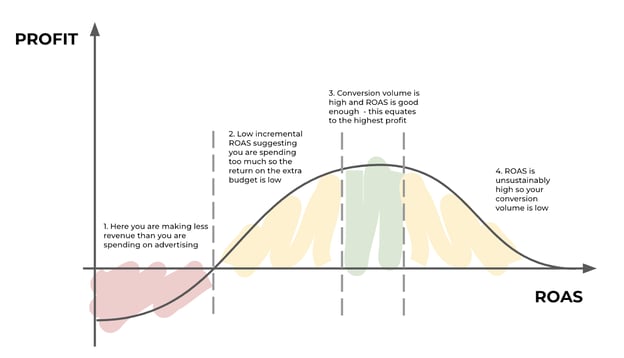

Not only can you push ROAS too high, as we have just seen, but you can also work towards a ROAS that is too low and sacrifice profit. The graph below visualizes this.

We can go into details for the best way to find this green, goldilocks zone of ROAS and avoid the other areas:

- Ensure your ROAS > 1 to avoid the red

- To avoid the yellow on the left, start measuring incremental ROAS. As we increase ad spend, our ROAS may remain acceptable, but we can still be making a loss on the additional amount we are spending.

- The final goal is to maximize and monitor your ROAS and conversion volume to ensure you aren’t pushing ROAS too high and sacrificing volume, as we have on the right of the graph.

In this example, spending more in March seems reasonable, considering we had a ROAS of 1.75, which is greater than 1. It appears to be an acceptable ROAS.

But, if you consider that the extra 200$ we spent between March and February only generated an additional 175$, you can see we are making a loss with this additional spend. We should drop back to spend of just 300$ as we were in February because we were more profitable at this ROAS.

To hit the green zone, keep increasing ad budget and calculating your incremental ROAS as you do. Spend as much as possible while your incremental ROAS is greater than 1.

Problem 2: ROAS is only focused on the short term

What metric reframes your performance to look at the long term?

The customer journey does not end when 1 item is purchased or 1 deal is closed. We forget the additional revenue customers provide when they return for a second purchase or upgrade their subscription next month. It is reductive not to consider the customer journey from start to finish. This is where LTV comes in.

Lifetime Value (LTV) is the estimated amount a customer will spend with your business throughout their lifetime. For example, if a customer purchases a copy of a newspaper for 2$, you might be led to believe that you shouldn’t invest much to advertise to people like this. If you reframe this to look at LTV, you might identify that most of your customers buy the same newspaper weekly for the next 20 years. In that case, one new customer is bringing an LTV of 2000$ - a significant difference.

Understanding the LTV of a customer allows you to better consider business profits and adjust your targeting for long-term growth.

To learn more about calculating LTV, check out our video:

Problem 3: ROAS assumes perfect attribution

What metric should we use to understand overall marketing performance?

One customer may first discover your brand through a Facebook ad. Then weeks later, they see an influencer talk about you on YouTube, so they Google your brand, click another ad, and browse your site. It’s not until a few days later that a display ad reminds them about you, and they make their first purchase.

We don't know exactly how much revenue advertising campaigns drive

This messy user journey is common. We can’t attribute every dollar of revenue generated to specific ad campaigns, yet ROAS attempts to do so.

Not only is it impossible to attribute revenue to one channel entirely, but upper funnel activities will always be treated less favorably with ROAS. Working towards conversion-oriented marketing metrics fails to consider the benefits of increasing brand awareness. Without this, growth can stagnate.

We need a more holistic metric that helps us understand marketing as a whole. The solution is MER.

Using MER to measure the success of your advertising efforts

Marketing Efficiency Ratio (MER) deals with total revenue divided by total ad spend from all marketing channels. It is similar to ROAS, but the difference here is that we are dealing with totals, no breakdowns by ad or channel, as we want to understand the holistic and cumulative effects of our complete marketing efforts.

When you shift from ROAS to MER, you leave behind the issue with attribution and instead focus on overall efficiency. Plus, you also resolve the issue of overly optimizing towards conversion-focused campaigns. This allows you to better understand results when you adjust your investment in brand building versus direct performance campaigns.

ROAS is like taking a magnifying glass and zooming in on all the details; it can be helpful but may also lead you to miss the bigger picture. MER is the missing metric which is all about understanding long-term strategy and seeing how your marketing efforts collaborate for results.

Now you have a few more metrics at your disposal, you can start incorporating them into your reporting and optimizing.

So what do I report on?

Focusing on the entire marketing funnel and understanding what drives business revenue is key for long-term brand growth. We can’t entirely reject ROAS and keep from checking CPCs. Instead, we need to analyze those numbers with fresh eyes, be aware of the potential pitfalls of marketing metrics, and view them side by side with metrics that matter. If you don’t have a way to measure and monitor LTV and MER, this is one piece of homework for you.

So what do I optimize ad campaign bid strategies on?

Sharing these downsides to ROAS is intended to broaden the current way you work with data - not to send you to an urgent flurry to change your bid strategy away from target ROAS.

For most lower funnel campaigns, with good quality data feedback into ad platforms, target ROAS is the best strategy for Google Ads for now. But we should strive to improve the revenue part of this calculation.

Can you use lifetime value here instead of basic revenue? Can you make these values dynamic and tailored to each customer and each region? Can you optimize on ad impressions or site traffic for your upper funnel campaigns instead?

Embrace change

Since moving away from ad delivery metrics to conversion-based goals, we have prioritized short-term results instead of thinking ahead to drive long-term growth. Marketers should widen their horizons to consider metrics more tangible to businesses when assessing, optimizing, and reporting on performance. I’ll stress this again: start getting MER and LTV into your metrics mix.

Finally, to come full circle before we wrap up here, the marketing landscape is ever-changing, and it would be unreasonable to assume this to be gospel from here on out. As the ad platforms evolve and the available data does, too, we should anticipate new changes in optimization and reporting best practices. For now, ROAS is on its way out, with MER and LTV coming to the forefront. But we’ve all got to stay on our toes because it won’t be long until the next industrial shift brings a new, better acronym.

-

Written by Kathryn Stockton

Written by Kathryn StocktonFrom performance marketing to operations, Kathryn has in-depth experience in marketing and a background working in digital advertising agencies.